- The Digital Product Passport promotes circularity and resource-efficient end-of-life management through standardized product information.

- Technology neutrality is essential; the DPP can be implemented with barcodes, QR codes, HF/NFC, or UHF RFID depending on use case.

- UHF RFID offers automation and throughput advantages for large-scale manufacturing and logistics, while HF/NFC supports consumer access.

- RFID will complement rather than fully replace barcodes, since cost and production volume determine the most suitable identification method.

Does RFID have what it takes to replace barcodes in the mass market?

From the foothills of the Alps to the world stage: Thomas Brunner heads Kathrein Solutions, a globally renowned provider of antenna and reader innovations. For him, sustainability is not just a trend, but a key driver, and the Digital Product Passport (DPP) is an important step toward greater transparency and resource efficiency.

In an interview with Anja Van Bocxlaer, Brunner talks about opportunities, challenges, and the key role of RFID technology for the Digital Product Passport.

1. Brake or booster: Does the DPP make companies more sustainable – or just more bureaucratic?

Thomas Brunner: I think the Digital Product Passport makes a lot of sense – especially in terms of the circular economy, resource efficiency, reuse, and savings. The aim is to have reliable information at the end of a product's life cycle: What can be done with it? How can it be reused or recycled? What is it made of? In my view, it is absolutely right that the European Union is creating a regulatory framework for this.

I therefore do not see the DPP as a restriction or a high cost factor for the economy, but as something clearly positive. For me, the advantages clearly outweigh the disadvantages. I wouldn't overestimate it – quite the contrary: I believe many people underestimate the opportunities it offers. Of course, not all industries are set up like the German automotive industry, which has been working with a large supplier network according to VDA standards for decades and has made its supply chain transparent – exactly what the DPP wants to achieve in other industries.

In the automotive industry, for example, there have been material databases for 20 years in which the composition of a component must be entered with 100% accuracy. This allows a manufacturer to say at the touch of a button: "This vehicle with this equipment is made of these raw materials." In principle, we are now pursuing the same approach with the DPP.

Of course, a small company with 20 employees and little digital infrastructure may initially be overwhelmed by the requirements of the DPP. But that must not mean that we do not further develop and adapt structures and processes just because there will always be companies that are not yet ready or willing to implement these changes.

2. Will the Digital Product Passport become a driver for RFID systems?

Thomas Brunner: Yes, I believe so. The DPP initiative is driven by regulatory requirements. When there are binding requirements, companies have to act. These requirements are strategically important for the European Union – which is precisely why they are being introduced.

Many companies have been working on automated recording technologies and digital, transparent supply chains for years anyway. The goal has always been to further optimize these processes and make them more efficient – a goal that has existed since the early days of the "auto-ID world."

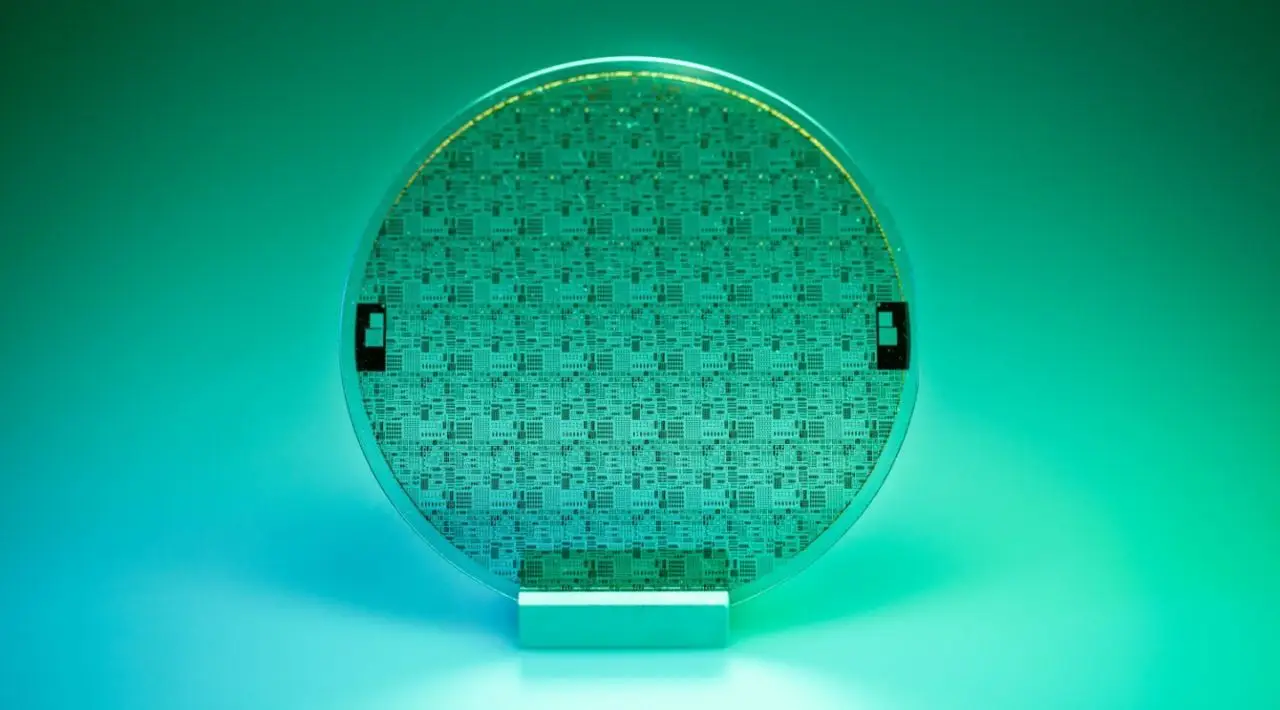

Investment in Europe is increasing year on year. We are seeing tremendous momentum in the number of transponder chips being produced. More and more industries – from retail and apparel to other sectors – are choosing to equip every product with a digital transponder.

When a company such as Decathlon has already equipped all its products with RFID, it is easy to meet DPP requirements via this medium. In this case, the investment in product tracking has already been made.

The DPP can accelerate this trend. While not every DPP solution will automatically be an RFID solution, it will encourage many companies that have not yet considered digitizing their supply chain to increase their efficiency. In my view, this will clearly have a positive impact on our industry.

3. That sounds very positive at first, but how can the DPP function work successfully?

Thomas Brunner: Standardization is essential for this concept to work. Only with uniform standards can a circular value chain be reliably implemented. I expressly welcome the fact that the European Union is consistently pursuing this path, regardless of when exactly the next steps will be taken.

4. Is it a mistake to limit the DPP to a single technology?

Thomas Brunner: Yes, that would be a mistake. In terms of technology, the DPP is designed to be technology-neutral. It can be implemented with a barcode, a QR code, or HF or UHF RFID, for example. The choice of technology naturally influences which scanner or reader systems are required.

This technology openness is of central importance to me – because not every product that needs to be labeled, and not every identification solution, is suitable for an RFID label. And not every application benefits from optical codes.

In order to make as much progress as possible, it is crucial to proceed flexibly. The task of the regulatory authority is to create clear, practical standards and framework conditions that enable the use of common and proven identification technologies.

5. The DPP is technology-neutral – yet the solutions compete with each other. What advantages does UHF RFID offer for the DPP?

Thomas Brunner: In my opinion, UHF technology is not yet sufficiently known in many areas, both technologically and economically, and is sometimes underestimated – especially in terms of its potential for automation, transparency, and increased efficiency.

In combination or interaction with the DPP, very good results can be achieved in supply chains and companies. This basically kills two birds with one stone. That is why it makes perfect sense to clearly position UHF as one of the possible technologies in the context of the DPP.

However, as a manufacturer, I do not consider it sensible to stipulate UHF as the only technology for the DPP. This would be unrealistic anyway, as it would lead to high investments – especially for companies that do not have highly automated or division-of-labor-based production or logistics.

Not every company in the European Union is set up the same way. The DPP should therefore enable different, sensible, and feasible solutions to meet the various requirements.

6. Will HF technology lose market share as a result of the DPP?

Thomas Brunner: No, I don't see that at all. HF technology is widespread and even more established – it is widely used in smartphones, for example. There will therefore be many implementations of the DPP with NFC solutions. I clearly see this as complementary and do not consider it expedient to play technologies off against each other – even if some associations would like to do so.

A higher-level association such as the VDI or the VDMA would never dream of saying, "Let's do everything with optics" or "everything with HF." There are simply different verticals and different degrees of automation in the industries.

Perhaps the DPP will also be available for food at some point. Take an olive farmer, for example: he probably needs a very simple solution that allows him to digitally identify and authenticate his product. In this case, it is not necessary to read thousands of tags at high speed in a fully automated process.

The situation is completely different for manufacturers who produce large quantities – such as kitchen appliances, household appliances, or televisions. They have highly automated production lines with corresponding potential for automated identification. Here, solutions that can be easily integrated into automated processes will be chosen.

If, for example, a manufacturer produces a preliminary version that is already packaged and stored in the warehouse, and only defines the final version upon delivery, this can be ideally implemented with dual technology. This allows them to give the device final firmware or a final setup through the packaging and use this as part of the DPP – for example, for regional restrictions on use or certificates. Such adjustments at the end can be implemented excellently with wireless technology – but not with a barcode, which does not work through packaging.

Each of these technologies has its own advantages, and the industry will want to use them accordingly. The task of the regulatory authority is to create a reasonable standard and framework so that common and established technologies can be used – naturally in compliance with safety standards. QR codes, NFC, and UHF meet these standards, ensuring the security required for the DPP.

The regulatory authority should enable broad use here. Then the industry can work in a technology-neutral manner and use the respective solution where it best fits the industry.

7. Will RFID replace barcodes in the mass market?

Thomas Brunner: For very inexpensive products or those produced in large quantities (e.g., disposable packaging or consumer goods), the use of RFID will not be economically viable – barcodes or QR codes remain the preferred choice here. Even though the cost of RFID tags is continuously falling, a simple paper label with a barcode remains cheaper in many cases. And especially when billions of items are involved, even the smallest price differences of a few cents make a significant difference in the overall calculation.

The choice of technology – whether barcode, HF/NFC, or UHF – will continue to depend heavily on the specific product, its application environment, and the economic conditions. The DPP will not replace these decisions, but it will transfer them to a uniform, interoperable system.

8. How relevant will the DPP be for end customers – and is a smartphone sufficient as a "reader" for this purpose?

Thomas Brunner: The DPP is not only aimed at logistical traceability, but also at enabling end users to actively retrieve information – for example, via their smartphone. NFC technology will therefore continue to be of great importance in the future, as every consumer will be able to read a product's digital passport with their own smartphone.

On the other hand, NFC and HF technology are less suitable for logistics processes. For this reason, every company will have to ask itself which identifier is the right one for the respective product and for the requirements of logistics automation. This means that the hybrid chip will become much more important in the future. The combination of UHF and HF technology makes it possible to achieve optimal performance in logistics and at the same time be read by the end consumer.

As long as there are no sufficiently powerful or widely available smartphones for consumers, HF technology will continue to be very important in the context of DPP.