- The digital product passport should be technology-neutral, with tagging decisions driven by application, cost and lifecycle requirements.

- RFID (UHF), NFC (HF) and 2D codes serve distinct, complementary roles; no single technology will cover all use cases.

- Europe's innovation and manufacturing capacity are stronger than media portrayals suggest, but regional production is needed to boost resilience.

- Frequency scarcity and proposals to repurpose UHF bands risk disrupting existing RFID-based logistics, requiring legal and standards advocacy.

Technology openness as the key to the digital product passport

Frithjof Walk has been active in the AutoID industry for 30 years. He is Chairman of the Board of AIM DACH (Germany, Austria, Switzerland) and AIM Europe and a member of the Board of AIM Global. He answers questions about the digital product passport not only from a business perspective, but also as a grandfather with an eye to future generations.

He advocates the technological openness of the DPP, but does not expect every product to be tagged with RFID in the foreseeable future. He also has more confidence in Europe's innovative strength than the daily headlines would suggest.

Market comparison: How are Europe and the US currently developing?

Frithjof Walk: From AIM's perspective, there is currently very close and good cooperation between Europe and the US. This involves not only technological developments, but also coordination on standards and communication protocols.

This cooperation is not only transatlantic, but global – the AIM community is also very active in Asia and other regions. The greatest uncertainty currently comes from tariffs and their constant changes – sometimes announced, sometimes reduced, sometimes increased. This makes it extremely difficult to make long-term assessments.

I am not an economist, but it is clear that tariffs ultimately lead to price increases and, ultimately, to global inflation. After all, tariffs are basically nothing more than tax increases. Whether it's companies or end customers – in the end, it is always the consumer who bears the higher costs.

In the European environment in particular, it is mainly high-end products that are produced in the B2B segment. In the consumer sector, these are often products that are considered luxury goods in other markets. Take Porsche, for example. A vehicle that is offered here for around €200,000 has long been significantly cheaper in the US – due to different taxation and market requirements.

If prices there now rise to $150,000, $170,000, or even $200,000 due to tariffs, it will still remain a luxury good that finds its buyers. In many cases, consumption will not decline sharply even if prices rise. In the long term, however, tariffs will lead to a shift.

The "America First" policy suggests that in the future, production will increasingly take place where the products are actually needed. In Asia for the Asian market, in the US for the US market. Of course, not everything can be manufactured everywhere, but the trend toward more regional production structures is clearly visible.

Resilience: How important are Europe's own resources and capacities?

Frithjof Walk: I consider this to be urgently necessary. Dependence on individual regions – for example, for semiconductors from Asia – is risky. We have seen how quickly supply chains can come to a standstill, whether due to a blocked bottleneck such as the Suez Canal or geopolitical crises. Regional capacities are therefore essential for becoming more resilient.

In this context, Europe is often portrayed as worse than it actually is. The media sometimes creates the impression that Europe is backward, whether in terms of digital technology or manufacturing. I strongly disagree with this. Europe is better positioned than many people believe. A look at the stock markets also reveals a more stable picture than is often conveyed in the media.

I am convinced that Europe will emerge stronger from this situation. The war in Ukraine has made it clear how important it is to build up our own resources and that we cannot rely on "someone somewhere" to produce them. At the same time, the debate about genuine sustainability will gain in importance – moving away from mere slogans towards real changes in mentality.

The bottom line is that I am confident. The coming years will be challenging for Europe, but also full of opportunities. This "wake-up call" can have many positive effects.

Frequencies: Is there a threat of competition for scarce radio resources?

Frithjof Walk: Yes, frequencies are limited. Today, almost everything runs wirelessly. Smart home devices, door controls, cars, and even washing machines that send a "I'm done!" message. Added to this are global communication systems via satellites and various navigation systems – GPS, BeiDou, and Galileo. All these systems operate in similar frequency ranges.

In the US in particular, there are currently efforts to use UHF RFID frequencies for stationary navigation. This would undermine UHF technology there. That is why intensive legal efforts are underway to prevent this. Organizations such as RAIN and AIM are strongly committed to this cause, because otherwise logistics chains and production control systems would be at risk.

Ultimately, it is a battle for frequencies. Bandwidth is limited, and everyone wants to use it, from the military to healthcare to everyday Wi-Fi.

Harmonization: Do we need global standardization of the bands?

Frithjof Walk: It is not correct to speak of a "frequency jumble". Rather, frequencies in individual regions are used differently for historical reasons – and are therefore blocked.

This becomes apparent when a new application is to be introduced, for example in the UHF range. In Europe, we use 868 MHz, in the US 915 MHz, because these bands were more readily available there. In Asia, on the other hand, other frequencies are common.

There are even differences within Europe. Some countries prefer one band, others prefer another. This makes harmonization difficult, even though we are well on the way to achieving it.

Current efforts in the US to run positioning via UHF frequencies, on the other hand, are something completely new – and very problematic for existing RFID applications.

The best technical solution does not always prevail. In the end, it is often capital and influence that decide, not technical quality. With sufficient financial strength, lobbying, or legal means, a technology can be placed on the market – even if there are better alternatives.

DPP technologies: Do we need NFC, UHF – or ultimately both?

Frithjof Walk: Neither technology will become dominant. There are efforts by individual market participants to use UHF tags everywhere. But NFC has other strengths, is based on a different concept, and is suitable for other applications.

UHF, on the other hand, enables greater ranges and is useful in logistics, for example, when it comes to identifying the contents of a package through its packaging. In other scenarios, however, HF – i.e., 13.56 MHz – is the better choice.

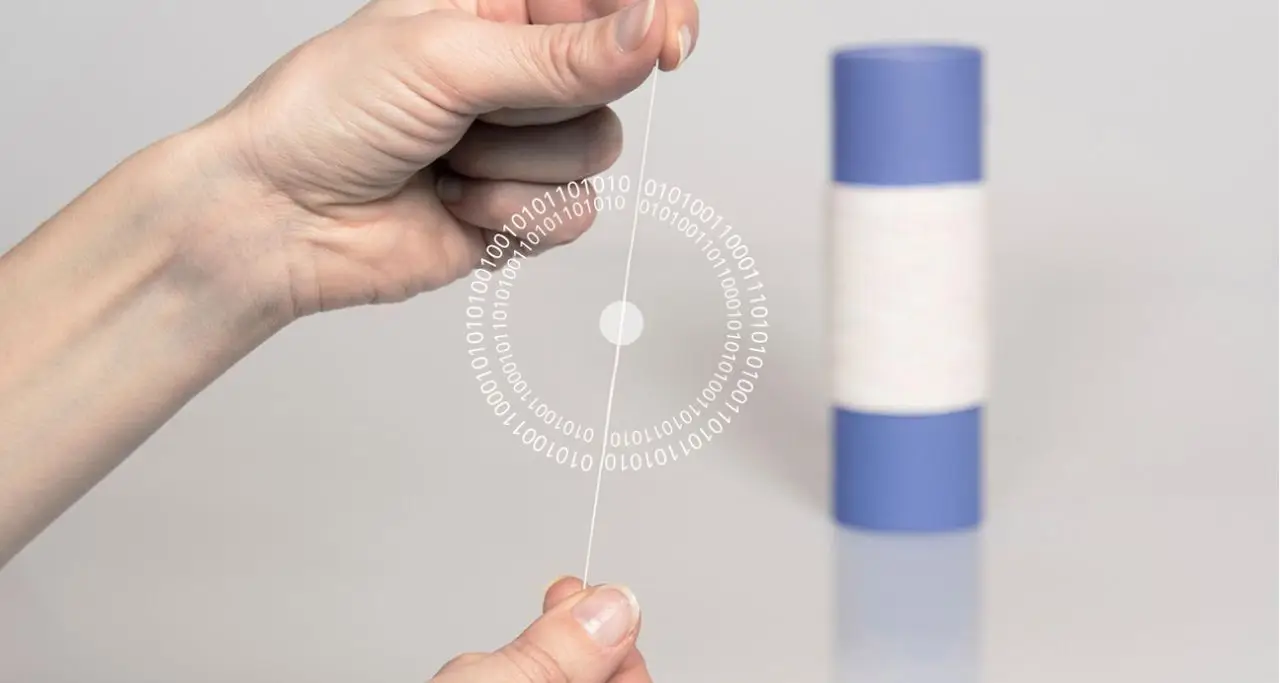

The application determines the technology. Ultimately, the DPP is just a link to a data source that must be assigned to a product. Linear barcodes are not suitable here because they cannot carry enough information. In contrast, 2D codes such as DataMatrix or QR codes can be used to access the data. The information itself is not stored in the product but is retrieved via the link.

For each product and each application, a decision must be made as to which coding is most suitable. This could be an RFID tag, but it could just as easily be a 2D code. It is virtually impossible to make a blanket prediction. Then there is the question of cost. An RFID chip costs money.

Should every disposable item – for example, in the fast fashion industry – really be equipped with a chip that costs several cents? Probably not. In this case, sewn-in labels with QR or DataMatrix codes will likely be used. Nevertheless, RFID tags are also used in the fashion sector to handle processes such as self-checkout, and NFC chips are used to verify authenticity.

Praxis: Why is RFID expensive in consumer goods but well established in industry?

Frithjof Walk: The situation is different in the industrial environment. RFID is already established in areas where production processes or logistics need to be controlled. Michelin, for example, has been equipping tires with RFID chips for around 20 years—because a permanently visible code on rubber is technically impractical.

RFID is also useful in plastic parts in the automotive industry, as it allows the exact type of plastic to be identified during recycling. In such cases, the higher product value justifies the additional costs.

There will not be one technology that covers everything. Rather, the application determines what is sensible and economical. This is precisely where the opportunities for our industry lie – in consulting, integration, product selection, and system operation.

Attention: Why is the world looking at the digital product passport from Brussels?

Frithjof Walk: First of all, I would like to disagree with that. It is not true that no one is normally interested in Brussels. If you ask me personally—not as a representative of an association—I see the digital product passport as a very positive approach.

As a grandfather, I think it's a good development. It's about sustainability and recycling. What can I do with a product when it has reached the end of its life cycle, and how should it be disposed of? This is not aimed at us, but at the generations after us.

Of course, people often have the attitude of "After me, the deluge – I want a good life, I don't care what comes later." But that is precisely why I believe the EU's efforts are very legitimate and important.

So why is the world interested in this? Quite simply, the EU is a huge market. There are more consumers here than in the US, and purchasing power is high. If Europe decides that products can only be placed on the market if they are labeled accordingly, then the "world" must comply if it wants to supply these markets.

Compared to Asia, Europe is smaller – we're talking about billions of people there – but many markets are not nearly as developed as ours. Europe, on the other hand, is highly developed, heavily regulated, and has strong purchasing power. That makes the European market attractive.

The world is interested in the digital product passport because the EU is a significant sales market and because sustainability and transparency are consistently demanded here.

Implementation: How does the DPP differ for consumer goods and industrial goods?

Frithjof Walk: The EU's central focus is on consumers. Consumers should be able to obtain information. The primary concerns are transparency and consumer protection. The key point is that the digital product passport must be designed to be technology-neutral. There must be no rigid specifications. Instead, the environment, the product in question, and its service life must be considered – and the appropriate solution must be derived from this.

At the same time, industry also has a role to play. In the B2B sector, the digital product passport will be used differently. The data it contains goes far beyond what is relevant to consumers. It includes recipes, production details, and confidential information that must be protected—keywords here are know-how protection, product safety, and the prevention of industrial espionage.

On the one hand, consumers need clear and understandable information. On the other hand, industry must be able to handle sensitive data securely.

Sustainability: Is the DPP more of a tool than a set of rules?

Frithjof Walk: People often forget that our resources are limited—whether it's oil or other raw materials. We're all aware of this, even if other issues are currently taking center stage. We'll still need products, medicines, and fuels in the future. That's why sustainability isn't just an overused buzzword, but a long-term necessity for all of us.